Ninety years ago tomorrow (19 December) the BBC began to broadcast to the world, or at least those parts of it that were coloured red on the map, as the Director General John Reith opened the Empire Service. In this post I look at the early history of the BBC’s overseas broadcasting, dip into some back issues of London Calling and present some programmes that have celebrated the history of the service.

From studio 3B in the recently opened Broadcasting House at 9.30 am on Saturday 19

December 1932, Reith broadcast to whoever was listening in on their shortwave

radios in Australia, New Zealand and Borneo. (1) In his live opening

announcement Reith talked about how this was a significant occasion in the

history of the British Empire. He continued: “There must be a few in any

civilised country who have yet to realise that broadcasting is a development

with which the future must reckon and reckon seriously. The more consideration

given to it today, the more experience gained, the more it will be realised

that here is an instrument of almost incalculable importance in the social and

political life of the community. Its influence will more and more be felt in

the daily life of the individual, in almost every sphere of human activity, in

affairs national and international.” “As to programmes”, he added (in an

oft-quoted sentence), they “will neither be very interesting nor very good”.

This was not

false modesty on Reith’s part. The broadcasts were an experiment but seemed, at

least in the early days, to mainly consist of music played from records,

interspersed with talks and ending with a news bulletin. A listener in Bermuda, used to hearing other

broadcasts from the States and Continental Europe wrote to say the programmes

were “inferior”, whilst a listener in Canada was of the opinion that it was

“feeble, asinine and hopeless for words.”

Not surprising when you consider that the Empire Service only had a

staff of six and a weekly programme allowance of £10.(2)

|

| Reith and BBC Chairman J.H. Whitley formally opened the Empire Service. |

Reith had to make that opening address a further four times – “I was very bored with it” he confessed in his diary - at 2.30, 6.30 and 8.30pm and 1 am the next morning as transmissions to different parts of the world started. First to India, Burma and the Federated Malay States, secondly to South Africa and West Africa, next West Africa and the islands in the Atlantic and finally Canada, West Indies and Pacific islands.(3)

The Director-General

had been keen to extend broadcasting across the globe for almost five years but

hit resistance from the Government as to how it should be funded – an eternal

area of disagreement and compromise throughout the history of the Corporation’s

overseas broadcasting. In the end the BBC was to foot the bill for the £40,000 shortwave

station at the existing Daventry site. (4)

What did

cement the reputation of the Empire Service was the Christmas Day message from

King George V whose broadcast was heard across the world, as well as the

National and Regional Programme. “Through one of the marvels of modern science,

I am enabled, this Christmas Day, to speak to all my peoples throughout the

Empire”, began the King’s speech, written for him by Rudyard Kipling. The royal

broadcast at just after 3pm followed an hour of Christmas greetings to and from

British “wherever they may be” in All the

World Over.

All the

Empire Service programmes were in English and were seen as a way of linking

together all the Brits scattered around the Empire. And it was essentially a

White British audience; the BBC Year Books of the time contain a table showing

the population of each country in each zone together with the “white

population”. Even so the General Overseas Service (as the English speaking

radio service became known) continued in this vein throughout the 40s and 50s

combining as it did a mix of programmes selected from the domestic services (the

National and Regional Programmes, and later the Home Service and Light

Programme), together with specifically produced fayre.

Within a

couple of years of its launch daily broadcasts were up to 16 hours a day and

would include music (light classics, popular and dance music, jazz and

variety), major events including sports commentaries, some talks and, most

popular of all news and the chimes of Big Ben. By 1934 the BBC had established

an Empire Orchestra of some 21 players with specially negotiated contracts to

allow for late-night and early morning playing, to account for live broadcasts

to different time zones. To allow for less reliance on the Home news team,

there was a separate news editor working with three sub-editors and the

beginnings of a Transcription Service providing pre-recorded programmes for

sale to overseas stations seen as “a valuable supplement to the direct Empire

Service” (more on that below).

Whilst the

impetus for the Empire Service came from the BBC it was political events in

Europe that drove the move into broadcasting in other languages. During the Second

Italo-Ethiopian War in 1935/36 the Fascist government in Italy set up a radio

station in Bari, southern Italy, that included anti-British broadcasts in

Arabic aimed at Egypt and Palestine where there was a strong British interest. In

the meantime the Ullswater Committee on broadcasting (reporting in 1936)

concluded that it was happy to see “the appropriate use of other languages

other than English.” Protracted discussions between the BBC, the Foreign Office

and the Colonial Office basically came down to funding and news values, the

Corporation not wishing to be seen as merely a propaganda arm of the UK

government. The funding compromise was an annual grant-in-aid (later on a 3-year

rolling basis) that was the main source of the External Services income until

April 2014. This did mean that the Government of the day was also able to

dictate the language services that the BBC should provide and, for many years,

the number of hours for each service.

The BBC’s

Arabic Service launched on 3 January 1938 although not without incident (5). A

Latin American service, seen as a counter to Italian and German broadcasts to

that part of the globe, followed on 15 March with 15-minute transmissions in

Spanish and Portuguese.

The

extension of radio services in French, German and Italian came about more or

less by chance at the time of the Munich crisis of September 1938. With minimum

preparation the Foreign Office asked the BBC to broadcast in those languages

the text of a speech being given by Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. The

speech was at 8pm. The BBC was asked to translate it and re-broadcast it only

two hours beforehand. In the Voices Out

of the Air documentary below, Leonard Miall relates the confusion that

occurred behind the scenes as the BBC tried to track down people to simultaneously

translate Chamberlain’s speech including the German cartoonist Walter Goetz who

was dragged away from a cocktail party having never broadcast before. After

that daily news bulletins in the three languages continued and by the following

summer they had become consolidated into a European Service.

World War II

saw an increase in the hours of the Empire Servicer and a significant boost to

the number and duration of language broadcasts: from nine languages over 44

hours a week in September 1939 to 40 languages over 230 hours in December 1941.

That wartime expansion led to a split on the BBC worldwide broadcast

administration between the Overseas Service and the European Service, which

would be the first to move into Bush House.(6)

The Overseas Service included the Empire Service (with five divisions:

Pacific, Eastern, African, North American, and British Forces) plus the Near East

Service and the Latin American Service. (7)

It was during World War II that a piece of music was first used that would, for six decades signify to listeners the world over that they were tuned into the BBC. That music was Lilliburlero. The old marching tune had been used as the theme for a 1942 Forces Programme broadcast Into Battle about the fighting spirit of Britain. The following year it was used as an interval signal by the Chinese Service. It was then appropriated by the General Overseas Service from 21 November 1943 to precede the news. It came about as part of an attempt by the BBC to help listeners identify which service they were tuned into. What was known as the Red network (Pacific, African and North American) used the notes B-B-C played on a celeste as an interval signal and Heart of Oak to precede the news. The Green network (the GOS) used Bow Bells and Lilliburlero. (8)

In 1949 a

Memorandum to the 1949 Broadcasting Committee described the BBC’s Overseas

output as: First “which is exemplified by the general overseas services in

English, is the provision for large and small British communities overseas of

what amounts to a Home service from Britain”. Second “programmes directed at

foreign countries” and finally “a third kind, not great in quantity but

nevertheless important, consisting of programmes addressed to nations or groups

within the Empire whose background and language are other than English”.

Dipping into

the London Calling listings for the

21st anniversary of Overseas Broadcasting here’s what was on offer

on the General Overseas Service for 19 December 1953:

You’ll spot some familiar programmes, Educating Archie, Much-Binding, The Archers etc. that were made for domestic audiences. I reckon at least ten programmes were also carried by the Home Service, Light Programme and even the Third Programme, including the rugby union commentary. Of course there are some anniversary specials with greetings from the Director General, Sir Ian Jacob, and the last of three features The Voice of Britain. Giving a talk on World Affairs is former diplomat and MP Harold Nicholson who’d been a regular broadcaster on both the domestic and overseas services, sometimes not without controversy (see blog post on Hilda Matheson). The Radio Princess, Princess Indira was making her usual parliamentary review in The Debate Continues. The inclusion of The Archers was not wholly welcomed by all listeners. A 1955 survey showed that recent exiles liked it but those who had not heard it back home were critical and “declared it unsuitable for overseas listeners or said it was wrong to present what they thought was an unfortunate picture of domestic life in England”. By the end of the decade it was dropped though not without an inevitable petition to have it re-instated. “How can the world’s agriculturalists keep up to date with the news of Ambridge”. (9)

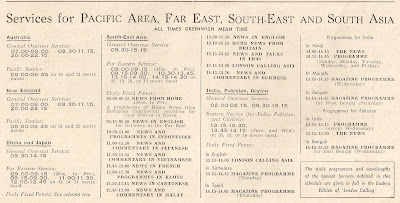

In this

Western edition of London Calling we

also get a glimpse into what was being beamed to specific regions of the globe.

Note the English by Radio programme,

a service the BBC introduced in 1942 and the use of “Calling” in titles. During

the week there was also Calling the West

Indies, Calling the Falkland Islands and

Calling Mauritius.

This section

lists the programmes for Europe in English and the vernacular services. Of

these languages the BBC now only provides Russian (online), Turkish and Serbian

(online). There’s also a French language service for Africa and a Portuguese

service for Latin America.

|

Further

afield the offerings for the Pacific and Asia:

In 1959 Martin Esslin gave this talk about the first 21 years of the European Service. Martin had joined the European Service during the war as a German talks producer. He’d go on to be Head of Radio Drama.

For the

External Services the 1950s could, in the view of Mansell, be described as a

“period of decline and lost opportunities”. There has cumulative cuts in

grant-in-aid since 1949, cuts in staff and language services, and transmitters

and aerials that really needed replacing or modernising.

From 1958,

under the newly appointed Head, Bob Gregson, the General Overseas Service made

the gradual shift away from focussing on a service for the Briton abroad (“audiences

in the Commonwealth, to British Forces, and to British communities overseas”

per the BBC Handbook) to one that would also cater for those for whom English

was a second language. This was in part a response to technology changes and

the increase in listening on transistor radios and in part a reaction to the

changing post-war geopolitical situation with the decolonisation of the Empire

and the Suez crisis (10).

The 1960s

would be “the decade of Africa” with the creation of a separate African Service

and, later in the decade, the building of a new Ascension Island relay station

to help shortwave coverage to West Africa (as well as to South America). Internally all the remaining services finally

moved into Bush House in late 1957 and there was also to be less dependence on

programmes from the domestic services. “We can no longer be merely an image of

the Home Service or Light Programme”, said Gregson. In May 1965 the name of the

service itself changed. It was no longer just catering for the Empire (or the

Commonwealth) but the world. So, in May 1965, it became the BBC World Service. (11)

Under

Gregson’s tenure there was also a “radical shift of emphasis to news, comment

and the background discussion of world affairs”. Some long-running programmes

starting in the era included the Saturday afternoon sports magazine Saturday Special (1959) with PaddyFeeny (changing to Sportsworld in late 1987), the “radio shop window for British industry" New Ideas (1958), Focus on Africa (1960), Topical

Tapes for rebroadcast by stations worldwide (1962),The World Today, Commentary, Science in Action (1964), Letterbox (1965), Outlook (1966) and World Radio Club (1967). To reflect the change in emphasis Home News from Britain was renamed News About Britain.

Back to London Calling and this time the edition

that coincides with the BBC’s 50th anniversary in November 1972.

Although

news has been the backbone of the World Service, from the mid-60s to the

early2000s it has always carried a full range of other programmes.

Drama:

plays, sometimes under umbrella titles such as Modern English Theatre, Theatre

of the Air, Globe Theatre or Plays of the Week with many of them

directed by the award-winning Gordon House. Drama serials some of which have

found their way onto Radio 4 Extra (The

Toff and Down Payment on Death

are recent examples). Even a soap set in a west London health centre called Westway.

|

| Script cover for a recording of a 1966 production of The Masters (BW) |

Music: request shows like Records Round the World and Anything Goes with Bob Holness. Pop music in Pop Club, A Jolly Good Show, Top Twenty and Multitrack. Rock music in Rock Salad with Tommy Vance. Jazz in shows with Humphrey Lyttelton or Steve Race and Jazz for the Asking with Peter Clayton (later Malcolm Laycock). Classical music in The Pleasure’s Yours with Gordon Clyde and Classical Record Review with Edward Greenfield. Any number of Radio 1 and Radio 2 DJs had shows including John Peel, Brian Matthew, Paul Burnett, John Dunn, Gloria Hunniford, Andy Kershaw, Ken Bruce and Steve Wright.

.jpg) |

| The presenters of Records Round the World pictured in 1969. Back l-r Sarah Ward, Don Moss, Colin Hamilton, Adrian Love Front l-r Gordon Clyde, Maggie Clews, Elizabeth London Chairing is Paddy Feeny |

Arts: magazine shows such as The Lively Arts, Theatre Call, Book Choice, Focus on Film and the long-running Meridian.

And before

this list gets too long some other programmes have included The Merchant Navy Programme which was

replaced by Seven Seas, the quiz Take It or Leave It with Michael Aspel, The Farming World, Waveguide, Network UK and

Omnibus.

For the 50th

anniversary of the External Services in 1982 it was not only a special cover

for London Calling but also a very

rare event, a Radio Times cover. The

accompanying article by Frances Donnelly helped promote the BBC1 documentary

(shown on 8 December 1982) Hang On, I’ll

Just Speak to the World, the title coming from announcer Keith Bosley as he

addresses the camera and realises he has a programme junction to announce.

You’ll find the documentary on YouTube uploaded by the producer Jenny

Barraclough.

The BBC also

issued an LP This is London narrated

by Leo McKern. This was adapted from the World Service programme Voices Out of the Air. It’s on the World

Service website under yet another title 50Years of Broadcasting to the World.

I’ve no

recordings marking the 60th anniversary (if you do please contact

me) but here are a few pages from the last ever edition of London Calling from October 1992. The following month it became

part of the BBC Worldwide magazine.

For the 70th

anniversary the World Service went to Table Mountain near Cape Town for 14

hours of live broadcasting presented by Heather Payton and Ben Malor. The

location was significant as it was the site of an early Empire Service link up

with the African Broadcasting Company for a “descriptive commentary by the

Johannesburg Station Director of the panorama from the summit of the mountain”

on 6 March 1933.

On 21

December 2002 the celebrations were reviewed in this edition of Pick of the World. The This

is London programmes mentioned in this programme are also online here.

In 2012 for

the 80th anniversary the celebrations were moved forward to February

as the World Service was now getting ready to pack up at Bush House and move

into the redeveloped Broadcasting House. On 29 February a number of programmes

were broadcast from the courtyard at Bush House. Some of these, including Outlook, World Have Your Say, World

Business Report and the live news meeting are online.

Here are a

couple of programmes from that day that are not available. First from 1000 GMT World Update with Dan Damon. Dan

presented this programme for 17 years but left the BBC in 2021 to become an

Ordained Minister for the Church of Wales.

From 1600

GMT World Briefing with Oliver

Conway.

It’s a low-key

affair for this year’s 90th anniversary, perhaps not surprising as

the BBC is yet again under the financial cosh and there are major cuts planned

for the language services, including the end of linear broadcasts for the

Arabic service. The Documentary with

Nick Rankin, listener’s programme memories on Over to You and a couple of editions of Witness History about Una Marson and broadcasting during the Cold War

seem to be the token offerings.

There are two other services whose history is inextricably linked with the Empire Service, and its later incarnations, that of the Monitoring Service and the Transcription Services. The monitoring of foreign radio broadcasts started on an informal level in 1937 with particular interest as to what was coming from Italy and Nazi Germany. In the summer of 1939 the Ministry of Information asked the BBC to undertake wartime monitoring and the service was set up with a base at Wood Norton. Initially heading the service was Malcolm Frost of the BBC’s Overseas Intelligence Department (originally set up in 1937 to conduct audience research in countries that the Empire Service was broadcasting to) later to become the Director of the Monitoring Service. The service moved to Caversham Park in April 1943 where it would remain until just over four years ago, moving into New Broadcasting House. You can read more detail about the early days of the Monitoring Service on Chris Greenway’s blog here.

As the

Empire Service often had to broadcast the same programme to different parts of

the world at different times it became an early adopter of recording the

original transmission for repeating during the day; what were initially called

‘bottled’ programmes (a term coined by the BBC’s first Chief Engineer Peter

Eckersley, though he’d left by the time the Empire Service launched). These

bottled programmes were either cut on discs (with a playing time of between 5

and 9 minutes) or recorded using the Blattnerphone system. At the same time the BBC was also looking at

providing radio stations around the world with a selection of its programmes on

disc. This would in part overcome some of the issues with shortwave listening,

help negate other station’s pirating BBC output and to generate income (albeit broadcasters were charged a nominal fee for the discs).

In July 1932 the BBC announced its intention to supplement the proposed Empire Service with recorded programmes. “These programmes, which will be produced with all the available artistic resources of the BBC, are to be recorded on discs and circulated to all stations overseas which subscribe to the service”. The advantages were: “the original programmes will be available for broadcasting at any time, and will be received by the local listener at perfect quality”.

The first

set of discs offered by the BBC included Cakes

and Ale, a programme of old English songs and choruses; Lily Morris,

Bransby Williams and Charles Coburn in vaudeville, with Henry Hall’s Dance

Orchestra; a dramatised biography of Christopher Wren; a programme of

traditional Scottish music; Postman’s

Knock, a British musical comedy written by Claude Hulbert; A.J. Alan telling

a story; A Pageant of English Life from 1812 to 1933; a Children’s Hour programme. Orders were placed from New Zealand,

Australia, India, Ceylon, Kenya, South Africa and Southern Rhodesia. A second

batch of discs was issued in 1934 and the Transcription Service was underway

under the leadership of Malcolm Frost as Head of the Empire Press Section (he

was also the post-war General Manager of the BBC Transcription Services).

Complications

arose at the start of World War II when the Foreign Office set up its own Joint

Broadcasting Committee (the director was the BBC’s ex-Head of Talks Hilda

Matheson) to provide British recorded programmes of a propaganda nature to

radio stations. The BBC was concerned that listeners may not be able to

distinguish between its own and JBC programmes but by October 1941 the services

were merged as London Transcription Services. By the end of the war it was

distributing programmes in nineteen languages to over 500 stations.

In 1946 the LTS became BBC Transcription Services and was based at St Hilda’s (a former convent) at the back of the Maida Vale studios. Programmes on offer were either specially recorded for TS or selected from existing programmes broadcast on the domestic or external services. They covered the full range of drama (the World Theatre series was particularly successful), comedy, talks, concerts and musical performances, documentaries, schools programmes and English by Radio. TS would either pick selected episodes from a series to be issued on disc or perhaps take the whole series – this has since been invaluable for repeats on BBC Radio 4 Extra were gaps in Sound Archives holdings can be filled using TS disc copies. Programmes recorded exclusively for TS included the long-running Top of the Pops presented by Brian Matthew and Pop Profiles (now both highly sought after by collectors) and the Vintage Goons series (1957-58).They also had a mobile recording unit available for concerts, including The Proms, and music festivals.

In 1964

Transcription Services moved to Kensington House in Shepherd’s Bush were it was

part of Overseas Regional Services (English), giving the Head of service the acronym

H.O.R.S.E. By the early 1990s all the masters were moved to Bush House and

eventually would find their way into Sound Archives, though with a great deal

of catalogue information missing. (12) BBC Radio International now provides a

similar service of licensing programmes for re-broadcast around the world.

(1) The BBC

had already dabbled with shortwave broadcasting setting up experimental station

G5SW at the Marconi works in Chelmsford, with the first major transmission to

Australia on 11 November 1927, By November 1928 the transmitter was in poor

condition and breakdowns were frequent but trial broadcasts seem to have

continued into 1931. Testing at the Daventry station had started on 14 November

1932 exactly 10 years to the day since the BBC’s first broadcast.

(2) Within

months the allowance had increased to £100 a week and by the end of 1933 it was

£200.

(3) Reith

wasn’t the first voice heard on the Empire Service; that fell to announcer William

Shewen who started with “This is London calling the Australian zone through the

British Empire Broadcasting Service at Daventry”. Shewen was the only staff

announcer for a while but by 1937 they had a team of five working in shifts and

where necessary sleeping over in one of the two bedrooms provided in

Broadcasting House. Other pre-war announcers, mostly ex-military types,included

Robert Dougall (later best known as a BBC tv newsreader), Pat Butler, former Talks Assistant H.P.K.Pooley, Hugh

Venables, Robin Duff (later a BBC War Correspondent) and Duncan Carse (the

voice of Dick Barton, Special Agent 1946-51).

(4) The

Empire Service site at Daventry included the main station building with a

transmitter hall, control rooms and offices plus five aerial array zones, one

for each of the geographic areas. Shortwave transmitting capacity was increased

at the start of World War II at Clevedon near Bristol, and Rampisham Down in

Dorset.

(5) The

first Arabic new broadcast on that opening day has been described as “the most

famous and perhaps the most controversial in the history of the Service”. It

included the item “Another Arab from Palestine was executed by hanging at Acre

this morning by order of the military court. He was arrested during recent

riots in the Hebron mountains and was found to possess a rifle and some

ammunition.” This seemingly innocuous

factual report sent shock waves though the Arab world and the Foreign Office.

“Is the BBC bound to broadcast to the Empire the execution of every Arab in

Palestine?” asked Rex Leaper, Head of the Foreign Office News department and

responsible for liaison with the Corporation. . The BBC took the stance that as

the item had been featured in an Empire Service bulletin it could see no reason

for not including it in the Arabic news.

(6) The

wartime overseas services found themselves scattered around bases in London and

over in Worcestershire. When land mines damaged Broadcasting House in December

1940 members of the European Service were re-housed at Maida Vale before moving

to Bush House in March 1941. The Maida Vale studios themselves took a hit in May

1941. Other bases were, at various times, at Wood Norton and also the nearby

Abbey Manor, Aldenham House in Elstree, and Bedford College in Regents Park. I

wrote about the studios at 200 Oxford Street in July 2017.

(7) The wartime changes to the Overseas Services are a little complicated. In November 1939 the Empire Service was modified “so as to make it virtually a World Service”, though the name Empire Service seems to have continued. In late 1942 it became known as the General Overseas Service. In February 1944 it merged with the Forces Programme to become the General Forces Programme meaning it was also available in the UK on the medium wave (see announcement in the Radio Times above). For home listeners the GFP was replaced by the Light Programme in July 1945 but continued on shortwave for troops outside N-W Europe. The old General Overseas Service title was back in 1947.According to the 1946 BBC Year Book “the BBC has always regarded the General Forces Programme as being contained within the General Overseas Service”.

|

| Photo BW |

(8) The colour coding of the networks persisted into the 1990s when Bush House still had a Green continuity studio. The European Service used the V for victory drum beats.

(9) That wasn't quite the end of The Archers for overseas listeners as in 1959 the Transcription Service offered slightly edited versions of the omnibus editions. A stash of these discs, 2,670 episodes were 'discovered' in 2003 and that story was told in Ambridge in the Decade of Love.

(10) In July

1956 the Government had established a Committee on Overseas Broadcasting

against a background of growing Foreign Office unease over the External

Services budget. The Suez Crisis that October was “the point at which the

strategic reassessment of the overseas services of the BBC became fused with

the problems of Britain’s evaporating influence in the Middle East...” (Webb)

(11) The new

name came not from the BBC but was included in the report of the Rapp

Committee’s 1964 report on “the methods and effectiveness of the External

Services”. Amongst the many recommendations on language services and relay

stations was the term BBC World Service which would have “more meaning to the

new audiences of English speakers around the Globe”. The World Service started

broadcasting around the clock in 1968.

(12) The Transcription Service masters included 16" discs, 1/4" tape and DATs. They were moved from Bush House in c. 2006 to the TV/Film archive in Windmill Road and then relocated to the new BBC Archives facility at Perivale in 2011.

Further

reading and listening:

In this blog

post I have only dipped a toe into the history of the BBC’s External Services. As

well as consulting back issues of London

Calling, BBC Year books and the Asa Briggs volumes I have also referred to

(and some quotes are taken from):

Let Truth Be Told by Gerard Mansell (Weidenfeld &

Nicholson, 1982)

A Skyful of Freedom by Andrew Walker (Broadside Books,

1992)

What did you do in the War, Auntie? By Tom Hickman (BBC Books, 1995)

London Calling by Alban Webb (Bloomsbury, 2014)

BBC World Service by Gordon Johnston & Emma

Robertson (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019)

I should

also mention Broadcasting Empire: The BBC

and the British World, 1922-1970 by Simon Potter (OUP, 2012) though I’ve

yet to find a physical copy that isn’t available for about £100.

For more on the history of Lillibullero there's this edition of Meridian from December 1998.

You can hear Reith's opening Empire Service broadcast on the British Library website.

Thanks also to Andy Finney and Simon Rooks for some additional information and to Barry Warr for the illustrations BW.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

1 comment:

Fascinating reading - thank you

David

Post a Comment