It’s no

accident that commercial radio, which is forty years old this week, was referred

to as independent local radio. “Commercial”

was a dirty word. Excessive profits were frowned on. The White Paper that paved

the way for ILR spoke of “public service” and stations being “firmly rooted in

their locality”.

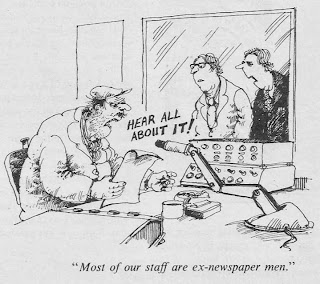

LBC was

mainly staffed with ex-newspaper men and women. And well-staffed, indeed

over-staffed, too: at the start there were about 150 on the payroll. Its headquarters

at Communications House in Gough Square were just off Fleet Street. In the

early days it struggled; it was under-capitalised, there were various run-ins

with the NUJ and, though it had plenty of newspaper experience, there was

little in the way of radio skills, and most of that came from “Antipodean

freelancers”.

Capital too

had some early issues. The initial music policy with its slant to the more “hippier”

stuff was not a success, there were spats with its London neighbour about just

how much news coverage it should take and in early 1974 the three-day week hit advertising

revenue.

Despite this

the stations were a hit with listeners: early audience figures showed LBC had

one million and Capital one and a half million. Though the Government’s plans

had been to introduce sixty stations they restricted this to just nineteen, at

least during the 1970s, with Beacon Radio the last the go on-air on 12 April

1976.

It’s against

this background that Ann Leslie wrote this piece, With an Independent Air, for Punch magazine published on 28 April

1976. It offers a somewhat metro-centric view of commercial radio; one suspects

she’d not heard anything of the other seventeen stations.

Elsie of

Westminster and I are getting a bit stroppy with each other over the airwaves

of LBC’s Nightline phone-in

programme, and she’s shouting into my earphones that them coloureds are

VICIOUS! VICIOUS” not like us native British what are more placid, not that

she’s got anything against black people mind you, there’s good and bad in all

of us, granted – but Ann, any spot of bother’ll set the coloureds off fighting

an’ that…

And in

between shouting back “But Elsie!” I’m coughing and blinking and waving my arms

about because I happen to have set the studio on fire.

Behind the

glass sits studio engineer Dave, a pleasant, professional lad who nevertheless

looks about fifteen and has the somewhat nibbled-looking hair of a typical Bay

City Rollers fan. Ciggie stapled to his lip, he gazes on, unmoved, as I flap

the air like a fire-dancer with flaming sheets of paper plucked from the

melting waster bin.

Had I burnt

the Nightline studio down, I’d have

cut LBC’s studio-count by half, but oh well, that kind of disaster is just

about par for the course for this, the first and most accident-prone of

Britain’s nineteen commercial radio stations.

Incidentally,

there isn’t an Ann Leslie spot on Nightline.

I’d merely wandered down with my notebook that evening into the pokey basement

huddled beneath the eighteenth-century elegance of Dr Johnson’s Gough Square

and found myself instantly lassooed into ‘guesting’ on the show. Had I been a

passing mouse, they’d have doubtless grabbed my tail, shoved a mike in my

whiskers and pushed me squeaking onto the air: LBC’s in need of endless free

squeaks to fill up the spaces between Alka Seltzer ads. Thanks to phone-freaks

like Westminster Elsie, they rarely run short.

Nightline’s

host is a nice worthy bearded chap called Nick Page (“yes I’m a practising

Christian”) who, every weekday night, dispenses four hours of spiritual

Ovaltine in his gentle foody voice to the lonely souls in London’s bedsitter land.

(Nightline, he believes, is partly

responsible for a decline in suicides in those trackless wastes).

So while I’m

beating out the flames, he’s fiddling with his blue cardie and soothing Elsie

down with “well, as you say Elsie I think there’s good and bad in everyone and

we’ll have to agree to differ on the other pints you’ve made, and now we’ll go

down to Putney and say hello to Ray. Roy? Hello Roy? Are you there? Roy? …

Well, we’ll come back to Roy in a minute. Over now to Marie in Battersea, hello

Marie! Marie? …”

And he and I

soldier on into the night with Maggie if Muswell Hill who’s against bingo

halls; and Ted of Shoreditch who says Lenin and Jewish bankers are responsible

for our “inflammatory money” and the decline-and-fall-of-this-once-great-nation-of-ours;

and Charles of St John’s Wood who says there’s too many black faces around and

Ann, are you as beautiful as you sound on the phone because if you are, tell

Nick to push off as I’m going to put on my pyjamas and come right over…

London has

two commercial radio stations – dear, worthy news-and-views LBC and the

all-music-all-fun Capital. “Capit-a-al! Capit-a-al” Capit-a-al Radio-o-o!”

sings the persistent radio jingle.

Capital has

pzazz! Capital has sex-appeal! Capital has MONEY! No apologetic lurking in the

basements for them: Capital prances manically about in the glossy splendour of

the Euston Tower and Capital has thick carpeting and digital clocks and DJs

like Dave Cash-by-name, Cash-by-nature and Capit-a-al! Capit-a-al! is wow! zowie!

b-boom!

Easter

Saturday morning and Capital is running its marathon radio auction to raise

money to “help a London Child” and its huge foyer is full of adenoidal Capital

fans gawping at leaping DJs and being frisked by security men and, up in her

office, lovely press-lady Sian is being photographed with Cliff Richard’s belt

and a Womble blanket and wow! even a Led Zeppelin tee-shirt donated by the

luminaries themselves!

And in the

studio, Kenny Everett and Roger Scott are howling and shrieking and jamming on

records and singing Hello Dolly for a

bet and it’s Capit-a-al! Capit-a-al! and thirteen phone lines are blinking and

in yet another studio Dave Cash is yelling “Great news! A Mr Crown has just bid

£51 for the Garrard record-deck – any more offers on that? – and there’s plenty

more wunnerful things coming up for grabs now! A snare-drum from the PINK

FLOTD! Twenty tickets to see Emmanuelle!

A personal horoscope from Terri King!

And, wait for it, a complete hair-transplant!” Capit-a-al! Capit-a-al!

And oops, here come the ads “Try the Big Fresh Flavour of Wrigley’s Spearmint

Gum!” and oh, wow! I haven’t the faintest idea what it’s all about, it’s just

Capit-a-al! Capit-a-al! Capit-a-al! Radi-o-o!

Commercial

radio was born at 6 a.m. on the morning of October 8th 1973 with the launch of

LBC; Capital took to the air a week later. Originally sixty such stations were

planned: the Government has now decided nineteen are enough. Most of the others

which have emerged so far have settled for varying combinations of the LBC and

Capital styles.

So how do we

assess the results of the last thirty months? Professional radio critics, of

course, instantly assume the facial expressions of men with knitting needles

stuck up their noses when asked to evaluate the wild pot-pourri of Gary

Glitter, fish-fingers, crossed-lines, Fred Kites, National Fronters, Zionists,

jew-baiters, corner-shop fascists, loonies who’ve lost their parrots and

pensioners who’ve lost their teeth, who’ve all come tumbling and gibbering down

out of the ether onto this green and garrulous land.

It’s “boring

old do-it-yourself radio”, jumble-sale-radio”,

radio-wot-fell-off-the-back-of-a-lorry”, and not what we were promised at all!

What were we promised? Well, what we were promised makes for merry reading.

What’s quite clear in retrospect – and should have been at the time – was that

British commercial radio was sired by a typically British marriage of

amateurism and hypocrisy.

Amateurism

decreed that those with the least experience in running a radio station should,

almost on those grounds alone, be selected for the job. Poor little LBC –

dubbed Radio Toytown – was expected to outdo the mighty Beeb in world news

coverage; soon virtually hysterical staff were collapsing like exhausted flies.

The Gough Square basement became radio’s Ekaterinburg, with the mass slaughter

of decent misguided programmes, followed by endless Stalinist purges of

idealistic Old Bolsheviks who’d taken their brief seriously and died under

machine-gun volleys from cadres of ruthless accountants.

Hypocrisy?

Well, God knows there was enough of that. Since admitting that you want to sell

anything and actually make money is a fearful social gaffe in this country, the

commercial radio lobby had to pretend that the last thing they wanted to do was get rich from selling fish-finger

eaters to fish-finger makers. Dear me, what a vulgar, gutter-press

interpretation of these noble gentlemen’s aims!

For a start,

they did wish people wouldn’t talk about “commercial” radio – it was

“independent” radio. Independent of what? Of the pointy-headed mandarins of the

Establishment Beeb, of course. Commercial – oops, sorry, independent- radio was to be a collection of brave little Davids

slinging pebbles on behalf of the

wonderful-little-people-of-our-great-democracy against the Goliath of the

Corporation.

Since

money-making was, like Queen Anne’s legs, not considered a fit subject for

polite conversation, the motives of the commercial radio lobby were draped in

yards of swishing verbiage about “community needs”, grass-roots feeling”, “

access”, “participation”, “the British People”.

Christopher

Chataway, the Tory Minister who legalised commercial radio, assured the

Doubting Thomases that “independent” radio was going to spurn the “pop and

prattle” of the BBC’s Radio One, and instead provide “a worthwhile service to

the community”. And Brian Young, Director-General of the IBA, movingly pledged

his belief that it would not all turn out to be “just the round of pop music

and plugs which disdainful critics have predicted”.

The IBA

issued “guidelines” to hopeful consortia scrambling for contracts. Like a rich

but bashful spinster letting on that she’s partial to chocolate fudge, Auntie

IBA then lay back and awaited her seducers.

The

seducers, having duly studied her tastes, told her what she wanted to hear and

then, the minute they’d bedded the contracts, told her to forget the chocolate

fudge promises on account of this is a hard world and such romantic twaddle

costs too much.

(Take

Capital, for example, which promised sweet music, serials, quizzes – all nice,

clean, short-back-and sides stuff. Auntie IBA might have liked it but hip young

Londoners didn’t, so it went out the window.)

So where are

all the shock horror probes into corruption in the local Parks and Cemeteries

Committees? And where the searing exposes of small-town sewerage politics?

They’re still there – but tucked away in the stations’ “social conscience”

slots at dead, unprofitable areas of the day or night when people are either

watching telly or are asleep.

As Tommy

Vance, a Capital DJ, told me, “Yeah, well, the, ah, incidence of Social

Idealism has to be strictly limited

in commercial radio: you gotta make a living right? Right!”

But this

large gap between stated aims and actual performance is not perhaps the only

reason for much of the critical response to commercial radio. Many genuinely

believed in such concepts as “grass-roots participation” and “media access” so

long as they remained concepts. I suspect that reality has dealt roughly with

much woolly-minded Fabian-bookshop sentimentality about The Grass-Roots and The

People. To these romantics, The People were symbolised by a kind of myths,

cloud-capped Noble Prole, like one of those chunks of socialist statuary

celebrating some Soviet Hero of the Best-harvest Norm.

It was

assured that once this Noble Prole was allowed “access”, his stout-hearted,

rough-hewn common sense and his natural feeling for fair play would emerge and

astonish us all.

Did it heck.

What happened when this Noble Prole seized hold of the air-waves was that he

gabbed on about deporting blacks in banana boats, sending squatters to labour

camps and shooting the Arts Council – in short, he turned out to be no more

noble or fair-minded than anybody else.

What’s more

he actually liked the “trivia and

pap” he was expected to scorn. He produced most of it himself: he wanted to

know what blighter in Tulse Hill had nicked his Cortina, and whether fin-rot

would kill his guppy-fish, and if any OAP in Willesden wanted an old piano, and

if Dave or Kenny or Mike would play Diana Ross’s latest waxing for Tracy, the

best wife in the world…

Now while

I’m a loyal listener, and indeed contributor to, Radio Four, I’m delighted by

the sheer serendipity offered by commercial radio. I love the chaos, the mess,

the rudeness, the prejudices, the unstructured, unsanitised anarchy.

It’s

occasionally very moving: how else can you describe the sudden upsurges of

kindness from listeners who, the night I was on LBC for example, rang in

desperate to ease the grief of poor Marlees of Lea Green who’d told us of the

cot-death of her baby son?

It even

produces bizarre flashes of surreal horror: as when a woman rang George Gale on

LBC to say she was worried about her nephew who celebrated May 10th every year

by buying a couple of parrots, stuffing them down his wellies, and plodging

around on them till they’re dead. And

since it clearly hadn’t occurred to her, George’s advice to send the parrot-plodger

to a doctor does strike me as a

“worthwhile service to the community”, if only to the community’s parrots.

But the

basic joy of commercial radio is that it provides a series of scruffy old

pubs-of-the-air where all classes unselfconsciously get together to share

gossip, misinformation, tell terrible jokes and say they know for a fact that… It’s no more, nor no less,

valuable a community service than that.

In the

London area, the various mine-hosts include grumpy old buzz-saw Gale, loony

little Kenny, sweet ‘n mimsy Joan Shenton, quirky Adrian Love, my very favourite (passed your driving test

yet, Adrian?) and that pompous old wind-bag David Bassett.

Which

reminds me, David. I’m Ann of Kentish Town and I’m a cat-lover and I’m furious

at what you said to that lady on Easter Sunday who wanted to know if her

neighbour was allowed to shoot her Siamese cat for trespassing… What? Hello?

Are you there, David? Can you hear me? Hello? I’m Ann of Kentish Town and I’m…

Punch finally

closed in 2002 with the archives being acquired by the British Library some two

years later. Back issues can, no doubt, still be found in dentist’s waiting

rooms. All copyrights acknowledged. Cartoons by Mac and Honeysett.

.jpg)

.jpg)